You can find it here

You’ll never guess…

Patreon content

If you appreciate the particular shade of humor one might find from listening to a cryptid react to humanity, might I recommend you see my Patreon’s $1 tier, the Spec-taters. The content I make for it is all meant to be simple and entertaining. So far I’ve read all of the terrible fan fictions My Immortal and Forbidden Fruit: The Temptation of Edward Cullen, featuring screams of rage and uncontrollable laughter.

I just began another series, called Cryptic, which covers all the items on my list of odd things I’ve experienced or heard about during my life. It will cover odd crimes, unexplained events, baffling disappearances, the truly weird. The first episode is now out, and is about the grisly murder of Mrs. Thomas, and addresses the baffling question of what happened to her head.

Organized ostracism

As I’ve discussed in previous entries, groups that are moving toward a single polarized expressed opinion on an issue, go through a number of transitions and evolutions. Familiar behavioral roles appear, and familiar patterns emerge as members jockey for consensus. Members of high rank exhibit opinions that lower ranking or new members rely upon because of a lack of information. Negative opinions hold more weight, because members of the group are attempting to avoid problems and conflict. So it is, that when a member of the group is declared to be aberrant by one or two members, the majority of members will often follow suit, to either maintain the “core” group, or to avoid conflict.

Religious groups, cults, and other extreme ideological groups often engage in shunning, or a kind of organized ostracism. If it were pursued on a one-on-one basis, it would be more commonly called bullying. Essentially, the leader or leaders of a group will make an argument—the validity of these arguments is irrelevant in this discussion, but in the case of polarized groups can be based on a mixed bag of supposed evidence, allegation, or outright lies—and then rally or cajole members of the group to participate in either completely ignoring the “offender”, or to participate in active censure.

Obviously, the experience of the bullied is important, and countless studies are done on the psychological impact of bullying and ostracism on victims. More importantly, in recent years, these studies have become an integral part of discussions about education reform, psychological counseling, and more pressing matters like gun control. However, what often isn’t discussed, is the impact organized ostracism can have on group members who perform the shunning, bullying, or ostracism. Even less explored is the negative psychological impact it can have on members of online groups, in situations that have a high degree of anonymity, and therefore deindividuation.

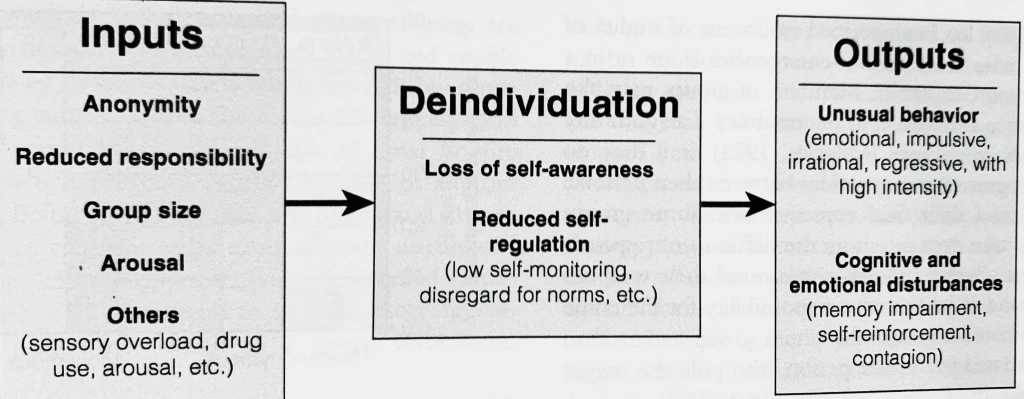

As discussed before, deindividuation is essentially a descriptor for the risky, increasingly cruel, deviant, or occasionally violent behaviors that members of a group engage in, when they feel they cannot be identified. But deindividuation isn’t merely I cannot be found out, so I can do as I please”. In a group, it can indicate that the actor feels so removed from their own identity, that they instead rely upon the group for identity. Therefore, a deindividuated person can often act on behalf of the group in extreme ways.

While it is true that leaders of extreme groups and cults organize the “corrective” actions of shunning, bullying, and punishment as a means of keeping an individual in line, the actions actually have multiple effects on the dynamics and psychology of the members. The obviously traumatic effects on the victim keep other members from deviating from the consensus, as they too do not wish to be punished. However, what has become increasingly clear in research, is that—I’ll refer to lower ranking members who are convinced to help ostracize as “participating bullies”—participating bullies suffer from horrible side effects themselves. Guilt and shame are frequently reported, and over time, the personality of the participating bully begins to break down.1 Multiple studies show that bullies suffer from lack of focus, inability to maintain relationships or jobs, increased risk for addiction and criminality, and so on2, but in the case of organized ostracism, the resulting breakdown of idenetity results in increased deindividuation, and therefore, a more controllable individual. Religious cults often insist that members bully any dissenters—and as may be expected, dissent is often any opinion that deviates from consensus—as a show of loyalty, but the side effect is, that as time goes on, and negative psychological effects occur, the participating bully becomes even easier to use in the service of the group. As the personality is broken down, the group member deindividuates, which almost ensures that as time goes on, they can be convinced to carry out more and more extreme actions.

The table above loosely describes how specific stimuli can effect a person who is a member of what is called a collective group—a mob, audience, or other emergent group. However, with some slight alteration, it also applies to members of other types of group. in the case of a group that is closed, or has a high interdependence, like a cult, “reduced responsibility” can often mean “lower rank”, for example. “Arousal” can also be seen as the emotional response to sermons, arguments, or targeted censure.

But how does this function online? Do internet-based groups also indoctrinate members to regimented abuse of dissenters? Do so-called “trolls” experience the same deindividuation and psychological breakdown? Will they, if their actions are undertaken on behalf of a group?

My instinct is to say of course, and that the anonymity and open social network structure of online groups actually contributes to greater deindividuation, and therefore more extreme bullying than would be performed in an offline setting. If the ostracization is organized or spear-headed by a leader or group of leaders, it may have almost identical effects as within groups like cults. For an example, I’d emphasize the social media platforms of beauty drama bloggers. Their specific role within the online community, the web of interweaving social media platforms, is to speculate, churn out rumor with little factual backing, and their own personal opinion. As their followings grow, the members, who cannot be identified by anything other than an online handle, participate in comments in an increasingly abusive way. If encouraged by the content creator, some even become violent. And because each member can have multiple platforms and multiple accounts on these platforms, a small group of “trolls” can appear to be much larger. This works toward the false consensus integral to polarized opinion.

While it’s true that a troll can be a part of many open groups (groups with little connectedness or organization) that doesn’t mean the negative psychological effects won’t take place. I think what is a good hypothesis to make is: the longer a person participates in trolling, especially on the basis of information put forward by a group or group leader, the more negative psychological effects take place. This almost ensures that their behavior will become more erratic, extreme, and could result in them being more easily mobilized by any online person they feel is an authority.

This is one reason I have always insisted people not defend me to any online presence. Interestingly only some platforms facilitate this kind of organized ostracism.

1. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/03/130305080452.htm

2. https://bullyingepidemic.com/how-does-bullying-affect-the-bully/

3. https://www.verywellfamily.com/the-effects-of-being-a-bully-3288472

4.https://www.talkspace.com/blog/trolling-psychology-bullying-help/

The psychological threshold for a social media group

In Group Dynamics, there is a concept called interdependency, which refers to the structural reliance on which a group depends. For example, in a factory setting, an assembly line worker cannot perform their step until the previous step is accurately completed. This is a high rate of interdependence. Conversely, a group that has no real tasks to perform but simply allows people to participate when they wish to, would not have a great deal of interdependence.

Interdependence doesn’t merely have to do with tasks. It can have a great deal to do with social identity, or how a person perceives themselves as part of or in relation to a group. If a person has no external connections outside the group, or is isolated from the core groups of their life like family, they are more likely to become dependent upon the group for their support. This is the sort of interdependence that is sought and indeed used as a control mechanism within cults.

The more interdependent the group becomes, the more a kind of connectedness must take place. The cohesion of the group depends on it. Groups in which every member has a close connection with every other member have the most cohesiveness and longevity. For example, in a family of two parents, three children, and four grandparents, this kind of cohesion can easily be achieved. It is not unreasonable to expect that one of the children can form connections to both the parents, both siblings, and all grandparents. These connections formed and maintained, the family unit is stable for the long term and interdependent on one another for support.

There is a mathematical equation that can render the total number of connections that must be made in a group, for any group to reach that familial style connectedness of all parties to all parties. It is:

n(n-1)/2

Where n is the number of members in the group. So calculating this for a family of say, 10 members, one gets a total number of connections at 45.

The larger the group, the more connections must be made to achieve that kind of cohesive longevity.

However, there appears to be a very well-defined limit to how many connections a human can form and maintain, and while individual members may have lower or higher thresholds (for example someone who is socially anxious would be more likely to hit their limit earlier) it seems fairly consistent across numerous studies with both observational and empirical data. Humans do not seem to be able to maintain connectedness, interdependence, reliance, or cohesiveness past groups that are 150 members in size as described by Dunbar in 2008. For centuries, humans have organized in increments of 100-150 members, from Battalions and legions to villages, and there was never a descriptive model to explain why. Dunbar’s research points to this cognitive limit as being essentially evolved into the species.

Plugging 150 into the above equation, we can see that a group of that size would have to have over 11,000 individual connections in order to behave like a family or core group.

Once that threshold is reached, members tend to leave or opt out of activities. The group fragments into smaller groups (usually before 150) and controversies arises between these. More conflict occurs and cannot be as easily mediated. This is a kind of chain reaction that can be seen, in which people fall into the predictable roles either to maintain the group or find fault with it. Maintenance roles tend to create new norms or rules and govern disagreements and reactions to the loss of members. As mentioned in a previous entry, blocking roles begin to make an appearance also. But the question is why. Why would a conflict in a group with a high rate of interdependence produce negative behaviors rather than positive? How would those behaviors trigger collapse of the group? And my personal question—how does the construction of the platform contribute to this cascade?

For me, classical ideas of “groups” tend to ignore social media networks, even refusing to define them as groups. This may have been applicable in the 90’s or even as recently as a decade ago, but in all honesty it no longer holds true. The platforms, however, have strictures to communication and gathering that the offline world does not. Thusly, classical models of behavior have to be shifted and changed not only to discuss online groups, but also to account for their growing impact on the lives of people.

Social media programs like chat rooms allow for a great many group dynamics to play out, and often, the size of the group is a factor in that. On platforms like Discord, for example, ranking members can be given authority, special roles that can create sub groups, and even the ability to kick or block others from the group. Direct messaging ensures the ability for individual relationships to form. Rules can be voted upon or determined by the server owner. All these features make it possible for a server to be run in a variety of ways, in accordance with any Parameter selected, but none of these offset the fact that the construction of the environment is essentially primed and ready to initiate negative effects.

The interactions, both intimate and large scale, can create a sensory overload, as can the speed of communication or subjects discussed. The group can police this, members taking up maintenance roles to effectively manage it, but once it reaches that psychological threshold, rules cease to matter. Controversies that had been dealt with will be used as justification, strategic positioning occurs, members who are confused will make a snap decision as to which person is right and which wrong. People will simply immediately fall into blocking roles, all logic aside, and the group will collapse.

It is somewhat arguable as to whether or not the sub groups that may form are still technically part of the larger group. They have dynamics of their own, but much of this may be either dependent upon the original group’s method of construction or in opposition to it, both of which are directly related to the original group. There is no data on how dynamics may continue to break down within smaller groups, if at all, but if blocking roles persist into extended groups, it may be possible that the cascade continues.

Social media may present users with the chance to make connections they wouldn’t otherwise, but very little understanding exists on how they can be constructed to best be in line with positive psychology. Much data shows that if the platform allows users to organize in a large group, the standard boundaries of group dynamics and group size still play out eventually, if in modified forms. It may be that some networks allow for a far higher psychological threshold, or even a far lower. Some other aspects of a platform, like Tumblr’s anon feature, may actually lower the threshold. The ability to tag people in posts—good or bad, can immediately trigger dynamics that might otherwise result more slowly within an in-person group.

More study is needed.

Does social media bring out the worst? Looking at the structure of platforms

The vast majority of study on group dynamics focuses on identifying types of social groups, how they form, the roles and activities within them, and establishes practical methods of group management to prevent a group from stagnating or disbanding; however, this exploration excludes social media, and how the structure of differing social media apps and sites create groups that either contributes to or varies from established group dynamics. Some apps may completely eliminate key group roles, causing certain theories about why groups form to become irrelevant. For example, if an app or platform does not allow people to group or “tag” entries by keyword, it becomes impossible to organize any group of followers or fans around that interest, almost ensuring that the special interest model of group formation becomes moot. Some other platforms allow organization around central concepts or interests, but discourage certain types of participation. For example, an app that makes it very difficult to share information to followers can completely destroy the cohesiveness of a group. Some platforms however, seem to encourage members of groups to occupy specific roles, just based on structure alone.

Group types are classified either as formal or informal, and are established primarily based upon the focus of the group—interest group, task oriented group, reference groups, and friendship groups are examples. Members tend to fall into a list of roles based on tasks or their dynamic with the group—roles that either maintain cohesion of the group, or can lead to its disbanding. Certain social media platforms could actually be selecting for one type of role over another, simply based on structure alone. This selection process can be large or small scale, or function differently on one scale than the other. An example would be any platform that allows larger groups to break into smaller groups—smaller subgroups behave differently than larger, and when decisions within smaller groups reach consensus, that opinion may clash with the larger group, causing disharmony. That disharmony tests the structure of the larger group and its ability to satisfactorily deal with concerns and make changes.

A platform like Facebook, is structured around a person’s real world identity, linking them to their existing contacts via associations. Friends of friends can connect to one another, but it’s seldom that complete strangers connect with one another. This ensures that each user sees a somewhat different side of people that are a part of their everyday life. It can cause real world relationships to break down over ideological issues. The commenting structure attributes the words said directly to the user and posts made are put up on the user’s “wall” again attributed by name. This kind of linkage to the real world often moderates behavior in some ways, but affects the types of things discussed. Facebook, in particular, because of its familial linkage, can actually create a strange interaction between weak and strong actors, creating friction for the user—for example, wondering what will happen if your mother begins talking through your wall, to a friend who knows some of your secrets.

Some social media platforms allow group discussions, while some merely adhere to a more standard structure of call-and-response—individual posts that can receive comments or likes. Some allow private versus public communication, and some allow the user to tailor the structure of their profile, to select for certain kinds of experiences.

But the real question is, can the structure of an app or platform not only help a group to form, but also select for odd dynamics, or ensure its fragmentation and breakdown. This question extends even further, into notions about what it may mean to communicate across platforms, where culture varies. The question brings up social issues about media exposure, polarization with real world consequences, and the overall experience of benefit received by the user. Are some social media apps simply designed in a way that brings out the worst in group members?

As groups begin to experience internal difficulties with dynamics— either surrounding an inability to agree to organization, or a disagreement about the goals, etc.—members fall into certain roles that are so predictable as to have names and general behavioral types. Roles that interfere with the cohesion of the group are called blocking roles.

The Aggressor – this role can actually vary considerably, but the overall behavior is ad hominem attack. This person can express disagreement with fundamental group values, be overly sarcastic, actively argue with the feelings or ideas of others, joke aggressively, tear down the status of other members, or dispute previously solved issues anew.

The Dominator – these members primarily assert control over others based on rank or asserted knowledge, They often engage in manipulative behaviors to attempt to acquire control over some section of the group—often to then leverage that smaller group against the cohesion of the larger group.

The Blocker – Blockers are stubbornly resistant to consensus, negativist, pessimistic, and refuse to accept group decisions, bringing them up repeatedly.

The Playboy – this person makes a show of their unwillingness to participate in the groups structure and maintenance. They often express cynicism of any compromise and will constantly absolve themselves of guilt if things “go badly”.

The Special Interest Pleader – this person engages in constant hair-splitting on behalf of a smaller segment of the group, or even a presumed segment for which there is no active membership. Through argument and persuasion, they succeed in making small points which have very little relevance to the group, into larger issues.

The Recognition Seeker – this person boasts constantly, will not admit wrong doing, refuses to be put in positions of lower status, they often engage in manipulation to keep control, if forced from it.

The Self-Confessor – makes use of the public stage to offer their own feelings or agendas which have little, if nothing, to do with the group’s stated purpose. This can throw off group dynamic and cause members feel socially obliged. This behavior also allows difficulties to be kicked-up whenever the person’s opinions contradict the group.

The Help Seeker – this person expresses overlarge feelings of uncertainty, confusion, self-deprecation, and other forms of manipulation to sway the group with sympathy.

Once these roles begin to appear within the group dynamic, it’s a fairly obvious sign that breakdown has begun. Any one of these roles can trigger the beginnings of a cascade effect toward polarization, which almost inevitably causes the group to fall apart. Recognizing these types of behavior can be an opportunity for group organizers to make changes that improve the robustness of group structure, but social media platforms that interfere with the leaders’ ability to adapt would prevent positive action. Indeed, some platform structures can actually encourage and select for negative cascades.

A good example of this is Tumblr, which allows any person not specifically blocked by the poster, to rebroadcast their negative opinions to their entire followership. This then can branch outward, each successive negative comment reblogged, going to another set of readers. This causes a traceable cascade effect toward polarization. It also actively selects for the specific roles listed above, as controversy tends to attract more attention. Tumblr’s ask feature also allows for anonymity, which encourages certain members of a fandom or followership to take up any of these roles from a place of relative social safety. Yes, this feature can be turned on or off, but it is still built into the platform. The structure of attribution also ensures that the poster receives notifications every time a reply or mention is made, which can ensure that every dissenting opinion becomes more relevant to the poster than is statistically warranted. Post structure, like Twitter, almost ensures that some posts become swift memetic movers or “viral”, exposing the poster to a variety of outside opinions that may influence the internal dynamics of their group or “followership”

Platforms that focus primarily on visuals like pictures or recordings often allow commentary among users. This creates whole new dynamics, particularly with regard to feelings of closeness to the content creator. Fan clubs are classified as “research groups” as they surround a primary interest but are not devoted to any task or action except appreciating, consequently, the opinion coming in is already polarized. An actor’s fan club, for example, is going to be devoted to that actor—“Stans”—and the group dynamic will be overtly and obviously unfriendly to anyone calling the actor’s behaviors into question. Thus, if a member of the group “defects”, the response to it will contain some portion of the behaviors described above. Platforms that facilitate commenting and tagging, naturally contribute to this. A good example of this would be “make up gurus“ of YouTube and the “drama channels” that follow them. The comments allow for stans of the creator to actively engage in arguments with those either pointing out problematic behavior, or expressing a dissenting opinion.

In standard group dynamics, the blocking roles are often integral to the polarization process—through which a group attains a single, extreme opinion on an issue—by attempting to steer the discussion through emotional manipulation. As said in a previous entry, when an agreement is reached about the central issue before the group, all other questions that arise within the group will obey the same behavioral models, simply because of precedent. The constant presence of people occupying those blocking roles will signal the disintegration of the group.

The primary focus of social media companies was always to build platforms that would contribute to connection, facilitate people coming together around specific issues, their every day lives, shared beliefs. I’m uncertain that much thought was put into how the structure of each app or platform would interfere with longer-term social networks. Facebook was only begun in 2004, Tumblr is 9, and so no long term data exists to measure group flux. How many times the platform assists a group in forming is immaterial, if it constantly also leads to the same groups disbanding. The more intimate the platform, the more insular. The more robust and connective the platform, the more negative behaviors are allowed to impact the core of a group. Most participants only think about their platforms as being a means to an end—a way to connect with others. They seldom consider that in fact, they may be exposing themselves to an environment built to cause constant social flux. If, as previously said in an earlier entry, a person has become ostracized or disconnected from their real life, and has inverted the relationship between weak and strong bonds, a platform that allows such flux could be inherently dangerous to the user for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is the constant exposure to negativity.

More study on how the platform structure affects the group dynamics is needed.

How digital insular social groups polarize and change behavior

Many people feel ostracized or alone in their everyday lives, a somewhat obvious thing to say. The internet has nooks and crannies and often people who have been on the fringes can find peers there. The anonymity offers equality—everyone is the same, and the etiquette is set both by the structure of the program, and by the ideological survival landscape—who is there. In a network like the defunct podium app, for example, white nationalists were more common and so the etiquette included all the common things you might expect from bigoted groups. On places like tumblr, ideas tend toward the liberal, and the etiquette becomes more astringently cautious about offense.

In sociology, social contagion theory specifically, relationships are described as either weak bonds/ties/actors or strong bonds/ties/actors. A weak actor is something that cannot change your behavior. For most people, what someone says on the internet is a weak actor, and a strong actor is a family member or a close friend. But on the internet, in these corners where outsiders collect, the relationship is often inverted. The rest of the world is a weak actor, and the anonymous people they’ve never met become strong actors on their behavior, their thoughts, their actions.

This is why the kind of social engineering being done by the Russians is so effective and dangerous, how it leads to insurrections and mob violence. It’s not merely that people believe things they see/hear more than once, or their assumptions about viable sources. It’s also that for many people, the cyberspace enclaves they populate become strong actors on their ideas. But the root of it is belonging. They don’t feel as if they belong, they feel like they are divided from others, they feel invisible in their everyday lives, they feel like their opinions aren’t heard or they cannot express themselves openly, and so the group they do have, becomes critically important. It’s also true that most outside information like news or random facts are usually absorbed through weak ties, because those casual acquaintances move in other circles and bring information back like bees returning to a hive. This is how internet social groups become insular—A space full of strong actors with no outside information. And as has been studied many times, insular groups tend toward polarized opinions—in this case not referring to duality, but an extreme perspective.

If a group focuses on a topic, they’re often referred to as deliberating groups. “As polarization gets underway, the group members become more reluctant to bring up items of information they have about the subject that might contradict the emerging group consensus. The result is a biased discussion in which the group has no opportunity to consider all the facts, because the members are not bringing them up.”1 Often deliberating becomes highly susceptible to localized “cascade effects” in which a piece or pieces of information, true or false, are spread through the group by higher status members on down the hierarchy (this status determined by expertise, age, presumed knowledge or any number of factors). Those with very little private information are overtaken by this cascade through informational externality– or the acceptance of the verity of facts based on a lack of desire to engage in confrontation, a presumption that the others know more, or that they must be wrong somehow. Often as ideas become more extreme, pressure is applied to conform, and members will allow even their own senses to be denied, in order to not be seen as part of the contested idea. This is called reputational externality. Both are means by which information is spread from one member of the group to another. Essentially, a cascade is so forceful it can often be seen as mimicking viral modeling. But acceptance of influence, susceptibility to it, isn’t uniform. It’s more likely to be uniform, if the deliberating group is a strong actor on a persons life. Meaning that if the group is seen as important to the person, their threshold for allowing a cascade to hit them is much lower.

“A further specific characteristic behavior within group dynamics is “groupthink”. It’s the phenomena within polarized groups, where concurrence-seeking and cohesiveness becomes so dominant that it tends to override realistic appraisal of alternatives. Groupthink replaces independent critical thinking. That results in irrational and dehumanizing actions directed against opposing groups.”2

In other words, deliberating groups, through complex dynamics, produce one uniform polarized answer, and if that group has become a strong actor on an individual…it changes behavior often in ways that mobilize them to be hateful or abusive.

But it’s all rather flimsy in actuality, because of that distance and anonymity. The lack of actual connection breeches many of the evolved cues of bonding—meaning the physical aspects of it like proximity, physical contact, hormone triggers for oxytocin, body language and so on. Without personal contact or a subject to deliberate, such groups usually collapse. To prevent that collapse, group leaders will often organize contact in the form of rallies, or protests. However, in social groups that are exclusively online, the groupthink produces things like retaliation campaigns such as letter writing, spamming, and negative press or reviews. The stronger an actor the group is in a member’s life, the more important the ideas generated within it become, until eventually, some see it as necessary to act independently on those ideas.

“…in a clinical study of 144 individuals who had threatened some form of violence against others, 8 were found to have threatened mass homicide… All 8 subjects said they had intended to kill as many people as possible, and all cases involved targeting a specific group against whom the would-be perpetrator held a grievance. Over the 12-month study period, none of the 8 subjects carried out or attempted to carry out their plans. However, 2 of the 8 assaulted a person unrelated to the targeted group.” 3

Obviously mass shootings are a rarer example of such actions, and are a statistical outlier. However, recent events make them a topic worth including. Extreme opinions and the group dynamics that help them to proliferate are caustic to the psyche. Often the group dynamic breaks down the filters and rational safeguards that inhibit action. As the social group becomes more of a strong actor in a person’s life, the ideas built there also become central. Without satisfactory organized paths or directions for the ideas, the groups do not often maintain cohesion. This collapse can also potentially function as a trigger for behavior, sometimes not even against the initial target of concern, by removing the support for those central ideas, something which could only exist in that deliberating group dynamic. Members are left with only an extreme idea, and a reality that cannot ever support it. This discrepancy is an obvious trigger also.

Understanding how the inversion of weak and strong ties happens, understanding how deliberating bodies work and what rules might be in place to prevent polarizing opinions, being able to see how these things are impacted or impact a digital landscape would be very useful indeed. Many of these things have undergone statistical analysis and can be somewhat predicted. Further research is needed.

1. “Deliberative trouble: why groups go extreme” Cass Sunstrin

2. “How social media causes disruptive group dynamics” Tony Saldanha

3. “Mass Shootings and Mental Illness” Agnes, Knoll

There are times I want to vanish.

Not die. Just cease to ever have been.

But we don’t age backward

And we don’t learn in reverse.

And we cannot unmake ourselves

Once we have been here

Because that is a paradox

where angels fear to tread.

We can forget where we have been

And that is as close as can be had

Patreon audio files can now be had at the lowest tier

Yes, I read them, through some slight alteration. I hope you enjoy them.

Find them here

EBook Version Available

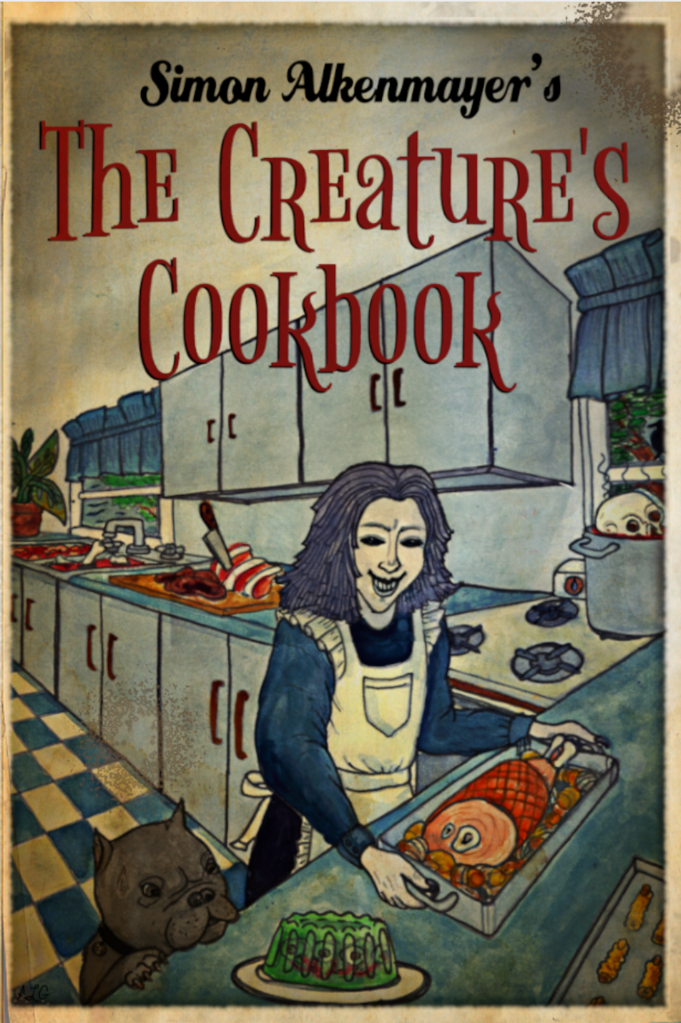

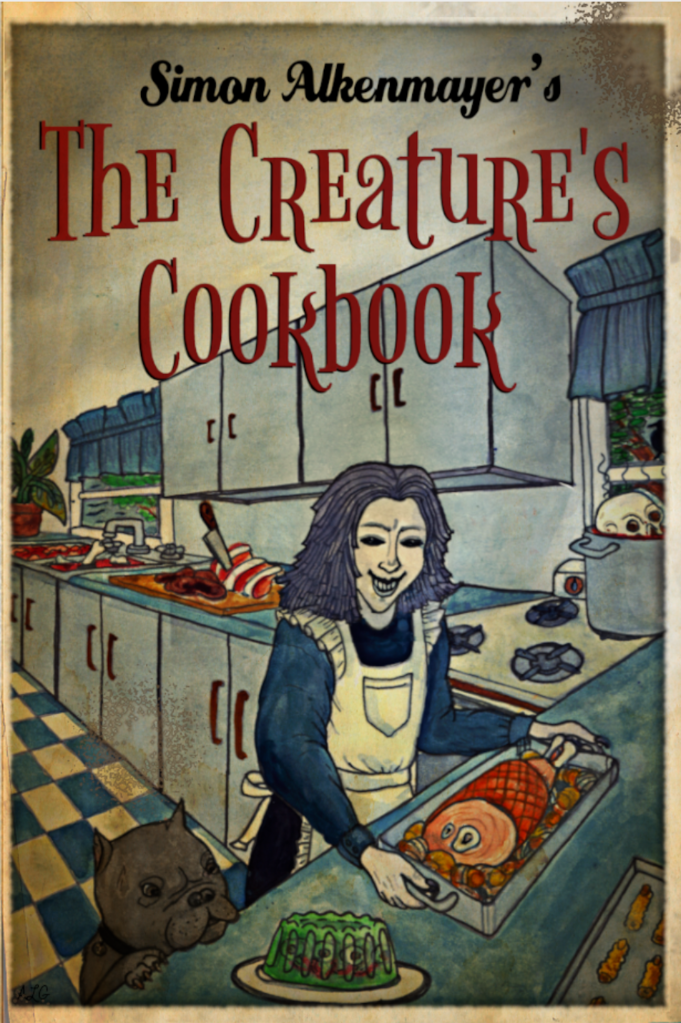

I have managed to finally make the ebook copy available! I’m not sure how long it takes to have everything synced up, but I have used Smashwords, a platform that distributes the book to all available formats for viewing, Kindle, Itunes, and e reader. So… You can now purchase an e-copy by going to any e-book marketplace and searching for The Creature’s Cookbook. You will see this cover:

Which was designed by Ann Groner, and inspired by classic cookbooks from the 50’s

The print copy will hopefully be available for purchase soon.

I will encourage you to purchase the book through Smashwords, as it allows you to choose how much you wish to pay, whereas other sites may have a fixed price, I have designated it as “Reader’s choice” to reduce costs. So please do contribute if you wish, to the experiment, otherwise, it is potentially free.